Week #10: Public Choice

02 Nov 2020Book: The Encyclopedia of Public Choice, by Charles Rowley & Friedrich Schneider (Springer Science & Business Media, 2004).

Soundtrack: “Mister Follow Follow” by Fela Kuti and Afrika ‘70

Something a little different this time: economics and politics instead of biology. I’ve been reading papers from a collection called The Encyclopedia of Public Choice, which is about how groups of people can best form collective decisions. Instead of summarizing a single paper, I wanted to talk about a few fundamental (but somewhat unrelated) ideas from this area. Most of this work goes back as far as the 1950’s, but they are all concepts that still get mentioned quite a bit.

1. The impossibility of choosing among three candidates

Clearly things in politics right now are very polarized, and so the question might have occurred to you: Would things be better off if there were three parties instead of just two?

In 1950, the economist Kenneth Arrow introduced what’s known as Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem, which suggests that having three options might only make things more difficult: When voters have three or more options to choose between, it is impossible (in general) to make a fair decision about who should be elected.

Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem generated a lot of controversy when it was first published. (The “proof” of this theorem requires a few assumptions that are up for debate.) But in general, the problem stems from the fact that when you have three or more options, there can always be voting cycles, which prevents you from choosing a winner. This was first written about in 1785 by the French mathematician Condorcet.

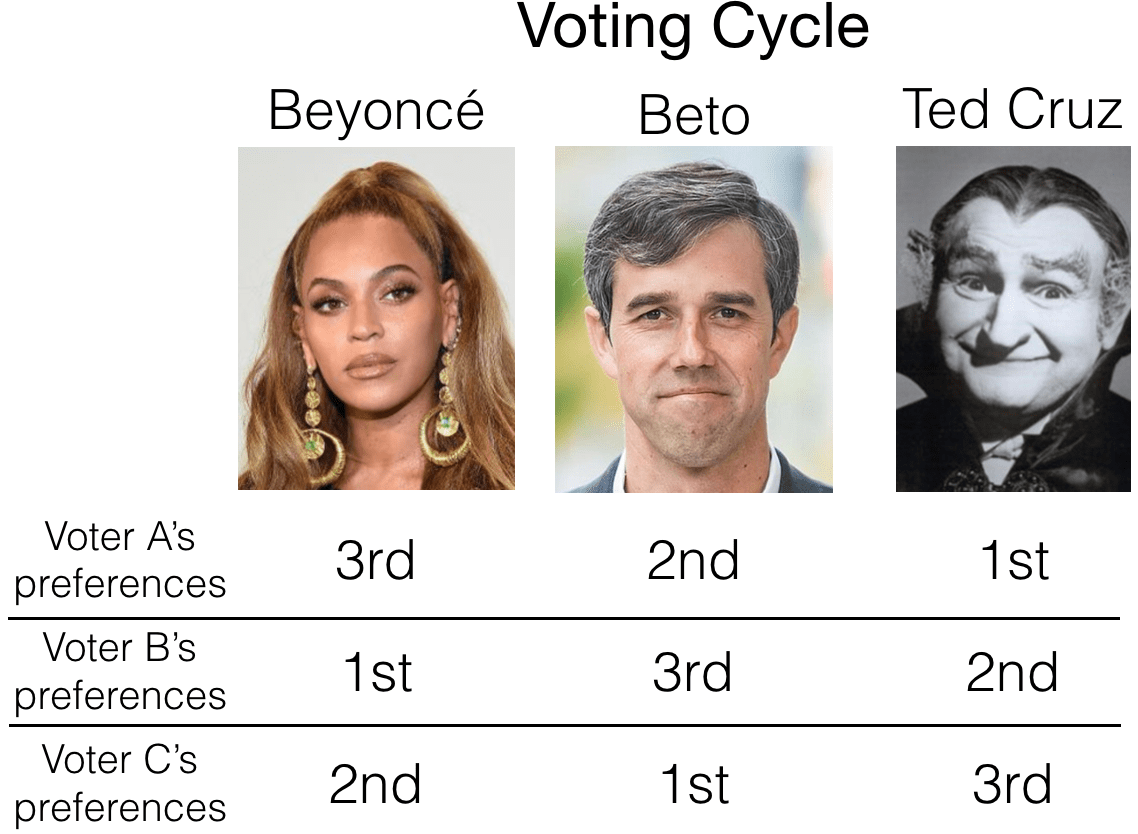

Voting cycles are like a game of rock-paper-scissors, except with political candidates instead of office supplies. Imagine we had a Texas Senate race between Beyoncé, Beto, and Ted Cruz, and prior to the vote we asked voters to rank the three candidates. An example with three voters is shown in the graphic. Which candidate, if any, can we say should be the winner of the election? More people prefer Cruz to Beto (voters A and B), so Beto can’t be the winner. But more people prefer Beyoncé to Cruz (voters B and C), so Cruz can’t be the winner either. But Beyoncé also can’t be the winner because more people (voters A and C) prefer Beto to Beyoncé! Every single candidate is less preferred than another candidate. That’s a voting cycle.

In this scenario, where we have ranked choice voting, we can’t choose a winner because of the voting cycle. With single choice voting, we can choose a winner, but not without causing other problems. This isn’t to say there aren’t plenty of problems with the current system, but it does hint at how having more than two candidates to choose from could make things even more complicated.

2. Pareto efficiency

Related to public choice is the field of social choice and welfare economics. Here the question is: How can we make economic decisions that consider the community’s well-being?

A key idea in this area is that of Pareto efficiency. If a system is Pareto efficient, it means that you can’t increase one aspect without decreasing another part. This trade-off comes about whenever resources are limited. In economics, Pareto efficiency is relevant when thinking about the distribution of wealth, because there’s only so much money in the economy.

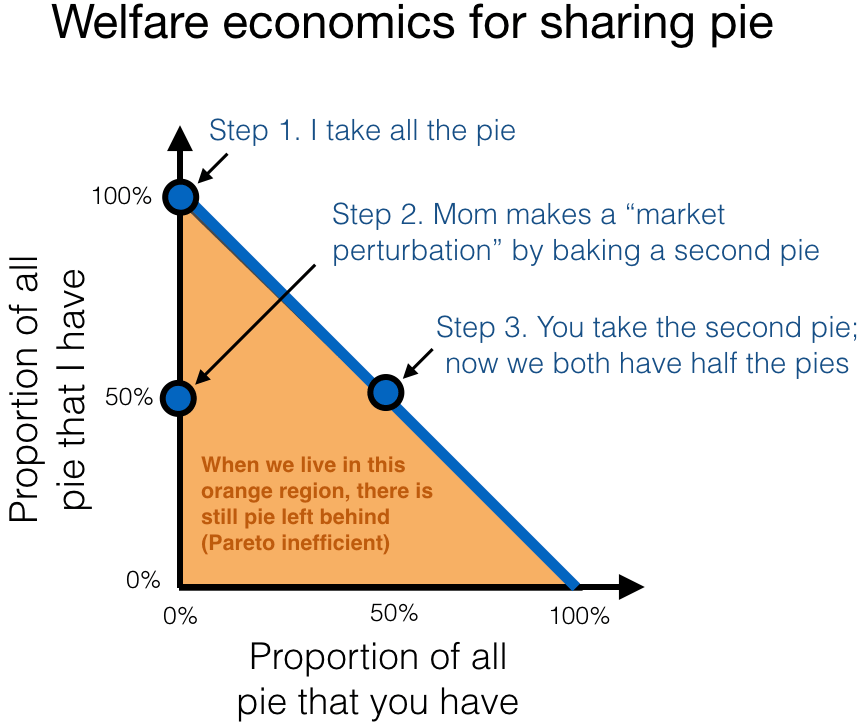

Instead of money, let’s think about pie. If you and I are trying to divide up a pie, then any solution that leaves no pie behind is called Pareto efficient. (In the graph below, that’s any solution on the blue line.) So for example, if I eat all of the pie myself, that’s Pareto efficient. It’s not necessarily fair, but it is Pareto efficient.

A typical assumption is that markets are efficient. This means any time the market is not at an Pareto efficient solution, the market will change until it becomes Pareto efficient. The perspecive of welfare economics is that we could fix wealth inequalities by taking advantage of the market’s efficiency.

For example, let’s say Mom bakes a pie, and I take all of it (Step 1 in the graph). You have none of the pie, which is unfair, but still Pareto efficient. What Mom (or the federal government) can do to fix this is to bake a second pie (or, inject some money into the economy, e.g., in the form of welfare). This will perturb the system away from its current position, to a position away from the blue line (Step 2). The market will then correct itself (e.g., you will take the second pie), which will place us at a new Pareto efficient solution (Step 3). The key here is to choose the perturbation just right so that the market’s “correction” leads to a more fair outcome.

There are clearly a lot of things being swept under the rug here in this way of thinking. For example, there’s nothing that prevents me from taking the second pie myself before you can get to it. (In other words, the market perturbation isn’t guaranteed to result in an improvement.) And how do we even tell if we’ve improved everyone’s general welfare? These issues aside, I think it’s an interesting way to think about the goal of welfare (or, stimulus checks!).

3. The median voter

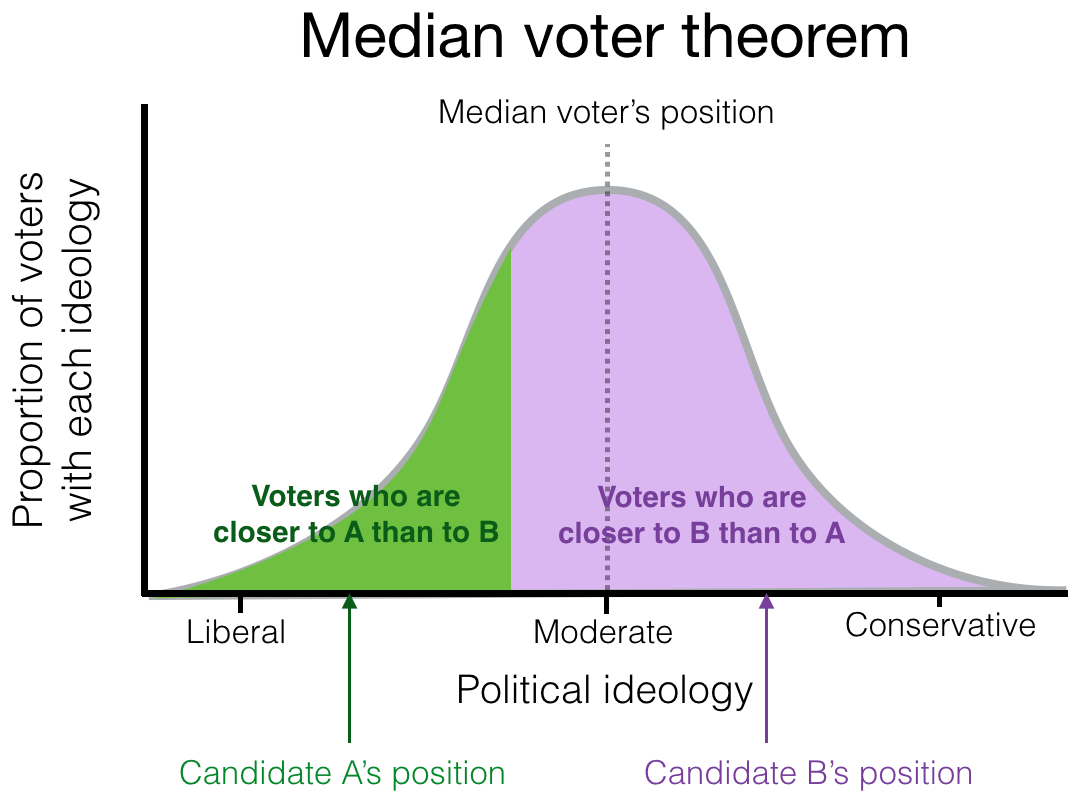

Another classic idea from public choice is that of the median voter. Here let’s imagine that we can describe everyone’s political position along a single axis. This is exactly what we’re doing when we describe someone’s political position as being somewhere in between liberal, moderate, or conservative. If you look across the population, there will be some distribution of this political sentiment, which we will say for now is shaped like a bell curve (see the graph below).

Now imagine that there’s an election with two candidates, each with their own position somewhere along this axis. Let’s assume that each voter votes for whichever candidate’s position is closest to theirs. The question is then: which candidate will win the election?

If the election is determined by a simple majority, then whichever candidate’s policy is closest to the median of the distribution will be the winner. Because of this, a candidate’s ideal policy is just to make sure that they are closest to the median voter. (A famous quote says that “parties formulate policies in order to win elections, rather than win elections in order to formulate policies.”)

Despite the fact that this model is incomplete, the idea of the median voter is still very prevalent in the way we think about elections. It explains why candidates are described as “moving towards the center” as their campaign continues and they learn more about who the median voter actually is. It’s also an explanation of why candidates often have more extreme policies during primaries than they do during general elections: The “median voter” in a primary will be different than the median voter in the general election, and so it’s more optimal in this sense for candidates to have different policies when the electorate is different.

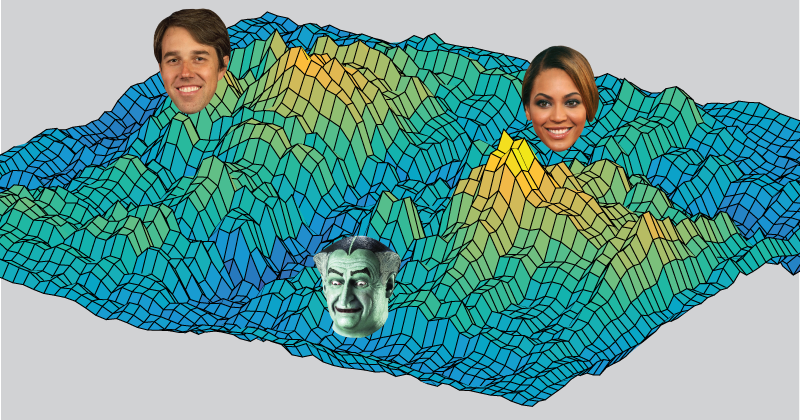

4. Policy space and controlling information

Of course, the assumptions of the median voter theorem do not apply in practice. For example, we’re assuming that there is only a single axis describing everyone’s political position, when in reality the full policy space should include our opinions about multiple issues. So what we really need is a multi-dimensional policy space, describing where each voter stands on the issues of immigration, abortion, government spending, and any other issue voters care about.

But an even bigger assumption is that voters’ policy positions are relatively fixed, while the candidates optimize their positions so as to maximize their chances of becoming elected. This might be wrong for two reasons. First, candidates cannot move their positions around too much, or else they’d be called out for “flip-flopping”. This keeps them relatively immobile in policy space.

Second, as we saw in the 2016 presidential election, voters’ positions in policy space are likely not fixed, but are instead open to manipulation. This leads to a whole new interpretation of the median voter theorem: To win an election, instead of changing your policy to match the voters, you could instead just change the voters to match your policy. As suggested by movies like The Social Dilemma, this may (in some sense) already be happening.

This emphasizes the importance of controlling information in politics. While we as voters may make decisions that are optimal given the information we have at any given point in time, the information we are being provided with is constantly changing. As some have suggested, “any theory of democratic decision-making must be more about information processing and less about preference maximization.” Hopefully more research in public choice will explore the role of information in forming collective decisions.

Summary

- Topic: Public choice, the theory of collective decision-making

- Why we care: Collective decision-making affects everything from PTA meetings to national politics

- The ultimate goal: Making decisions that are fair for all involved parties

(Un)related links

- brief overview of voting paradoxes

- Pareto efficiency in James Harden’s stats

- The Ides of March, a 2011 political drama that I love for reasons I’ve never really understood

- Frontline’s The Facebook Dilemma