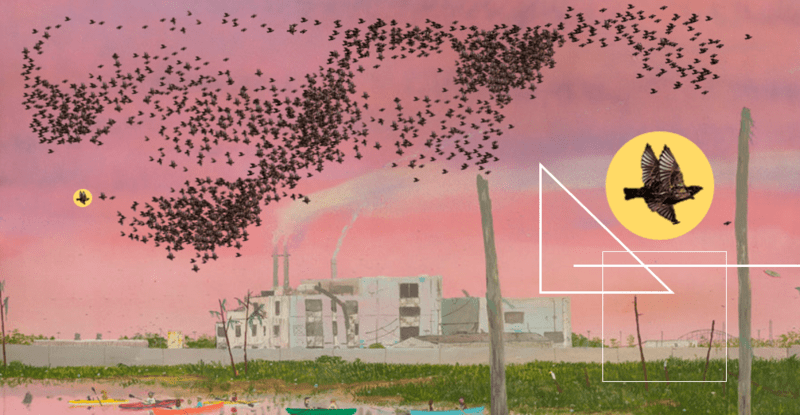

Week #9: Swarms and Flocks

08 Dec 2018Paper: Scale-free correlations in starling flocks, by Andrea Cavagna et al. (PNAS, 2010).

Interactive: Boids and Bugs (by me)

A frequent theme in science is trying to understand how complexity can arise from simple rules. And flocks of starlings might be one of the most striking examples of just how wide the gap between simplicity of rules and complexity of the resulting behavior can be.

Of course, starlings aren’t the only species that shows collective group behavior. In general, there’s also:

- flocking in birds

- schooling in fish

- herding in cattle and other mammals

- swarming in insects (and bacteria)

One of the most interesting aspects of collective behavior is how new abilities emerge at the group level that are not present in any individual. (More on this later.) Understanding how such a thing is even possible has attracted scientists from a wide range of backgrounds, including biology, physics, robotics, and mathematics. This week’s paper is a perfect example of how all those subjects fit together.

Boids

One of the first big steps towards understanding flocking came in 1986, when a computer animator named Craig Reynolds* made a computer program to simulate bird flight, which he called Boids. His model of flocking involved three basic rules:

- separation/repulsion: avoid collisions

- cohesion: stay close to your neighbors

- alignment: move in the same direction as your neighbors

(*The Boids program was used in Tim Burton’s Batman Returns to simulate bat swarms, and Reynolds later won an Academy Award for his pioneering work using computer animation in films.)

How do these three rules interact to create such a complex result? It’s easiest to think about what might happen if we had a system with none of these rules, and then we can see what happens when we add each rule in turn.

How do these three rules interact to create such a complex result? It’s easiest to think about what might happen if we had a system with none of these rules, and then we can see what happens when we add each rule in turn.

- No rules: You can think of a gas as a collection of particles that obeys none of the Boids rules. The result is random, incoherent motion.

- Rule 1: If you give your particles the first rule above–a sense of personal space–they start to act like flies. Each fly goes basically wherever it wants, but it has the decency to avoid collisions.

- Rules 1+2: Next, give your flies cohesion, or a desire to stay close to the pack, and you have a swarm.

- Rules 1+2+3: Finally, when the bugs in your swarm try to align themselves with their neighbors, so that everyone’s flying in the same direction, that’s when things start to look like a flock.

Play around with these rules yourself with Boids and Bugs, an app I made which builds off of the original Boids. (You can also use your cursor as a predator to try herding the little particles.)

Why flock?

Boids is a simple model of how collective behavior can emerge from simple rules. But is it really how things work in the wild? What makes this topic especially interesting to me is that it’s only in the last ten years or so that anyone’s had the technology to collect sufficiently detailed data from actual bird flocks. In this week’s paper, the authors used multiple cameras set up on the top of the national museum in Rome, and used 3D tracking to capture the flight trajectories of individual birds in a flock of thousands.

Most people believe starlings form flocks for protection against predators. How does flocking offer protection? If a hawk swoops towards part of the group, it’s likely that only the starlings closest to the hawk will actually see it and try to escape. But the alignment rule above will enable the group to react as a unit. If all of the starlings are strongly aligned with each other, the flock will be able to turn away as one, despite the fact that most starlings won’t have even seen the hawk.

One potential problem is that starling flocks can get incredibly large, sometimes containing up to a million birds. In large flocks, are two birds on opposite ends of the flock still in alignment? It’s possible that if every bird simply aligns itself with its immediate neighbors, the entire flock can stay in sync. On the other hand, it may be that once the flock gets sufficiently large, birds that are far enough away will no longer be aligned. To assess how well aligned the flocks were, the authors measured the correlation between the flight direction of every pair of birds, and looked to see if the correlations were weaker in larger flocks.

Starlings playing Telephone

As the authors explain, alignment in flocks is like playing a game of Telephone, in which each person passes a message only to the neighbor immediately next to them. To allow the message to spread throughout the group, you need each message to be passed without too much noise, or error.

Of course, the more people you have playing Telephone, the harder it will be to send your message all the way through the group without it being corrupted. Similarly, the larger the flock of starlings, the less likely it is that information about a predator can make it to birds on the other side of the group.

What the authors wanted to know was how far this information can travel in larger flocks. Specifically, how far apart can two birds get before they become uncorrelated, or un-aligned? Or in terms of Telephone, how many times can a message be passed before it becomes unrecognizable?

Surprisingly, the authors found that the larger the flock, the further information could travel. In other words, the larger the flock, the stronger the alignment among nearby birds. This suggests that correlations in starling flocks are roughly ‘scale-free,’ because as the flocks get larger their correlations get proportionally stronger. Scale-free correlations may explain how flocks of millions of starlings are still able to act as a cohesive whole.

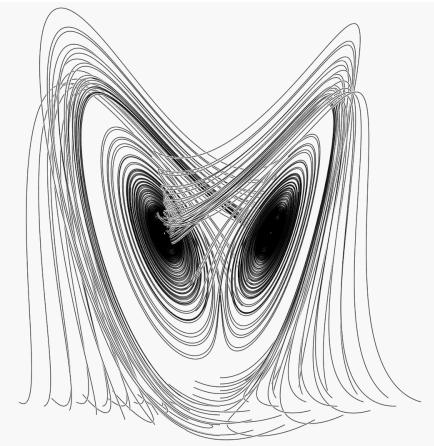

Self-organized criticality

You might be wondering why physicists and mathematicians are interested in understanding how a bunch of birds fly in groups. The reason is that flocks of starlings appear to strike an interesting balance between sensitivity and robustness. This can be described by an interesting mathematical property, called criticality, also found in many other complex natural systems.

One example of criticality will sound familiar: When water is boiled it undergoes a phase transition into water vapor. Near that transition, around 100º C, it’s said to be at a critical point. Many other systems have critical points as well. For example, snowy mountains move towards a critical point as they amass more and more snow before things transition into an avalanche. The same is thought to happen before earthquakes. Some even argue that the brain may be situated at a critical point '’between dead and epileptic.’’

One appealing but unproven theory is that biological systems might have evolved to operate near criticality. The reason is that, near criticality, systems can achieve a unique balance: not so sensitive that the slightest perturbation causes chaos (as in an earthquake, or epilepsy), but not so robust that they’re unresponsive (like a mountain, or a dead brain).

Scale-free correlations, as observed in this week’s paper, are a trademark of systems near criticality. While it is not known for certain whether starling flocks are truly operating near a critical point, other work has found additional theoretical support of the idea.

Summary

- Topic: Flocking in starlings

- Ultimate goal: Understanding the principles governing coordinated behavior within groups of animals

- Key observation: Simple rules can simulate flocking, but actual animal behavior is often far more complex than it may appear at first

Related links

- Starlings vs. falcons in the last episode of Planet Earth II

- A man who flies alongside migrating birds

- If Birds Left Tracks in the Sky, a photo gallery

- Are Biological Systems Poised at Criticality?

- Collective Behaviour without Collective Order in Wild Swarms of Midges

- Emergent dynamics of laboratory insect swarms