Week #8: Cochlear Implants

09 Sep 2018Paper: Cochlear Implants: System Design, Integration and Evaluation, by Fan-Gang Zeng, Stephen Rebscher, William Harrison, Xiaoan Sun, & Haihong Feng (IEEE Rev Biomed Eng, 2008).

Soundtrack: “Boléro” by Ravel

A Crackling and Boiling Sensation

Apparently if you put two ends of a battery to your ear, you will get shocked. You will also hear “a cracking and boiling sensation.” That sound is not real, in the sense that someone sitting right next to you would not hear it. Instead, you hear it because your brain interprets the electrical current being sent from the battery to your auditory nerve as a particular sound.

The goal of your peripheral auditory system is to convert the sounds around you into patterns of electrical activity that are sent to your brain. Because your brain processes information via electrical impulses, anything that provides your auditory nerves with the appropriate patterns of electricity will be interpreted by your brain as sound. Zap it a few times in one way and it might sound like a car driving by. Zap it a few times in another way and it will sound like human speech. And in a way, we have cochlear implants thanks to the Italian scientist Volta shocking his ears with a battery in the late 18th century.

A Brief History of Cochlear Implants

Cochlear implants are a relatively recent innovation. Back in the 1950s, scientists were essentially still zapping their patients’ ears with electricity to get a better idea of what was going on. In the 1970s, there were a few reported success cases, but the NIH deemed cochlear implants “morally and scientifically unacceptable” due to their questionable efficacy.

Things have come a long way sense then. By 2001, nearly one out of every ten children with severe deafness received a cochlear implant. (Cochlear implants usually cost around $50k, but are almost always covered for children with health insurance.) These children, who would otherwise be profoundly deaf, are able to grow up and perceive speech at the same level or greater that you are able to understand speech on a telephone.

In fact, people with cochlear implants can hear and speak so clearly that you would likely not even guess they were hearing impaired. You’d probably just think they had a foreign accent, as you can hear for yourself in this great video recently published by The New York Times. But turn off the little electrical device that sits behind their ears, and they are immediately unable to hear, and unable to speak as clearly.

A microphone, a battery, twelve wires, and a computer

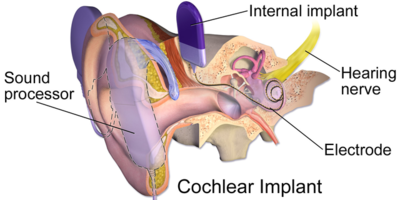

A cochlear implant is basically an electronic device to replace a patient’s peripheral auditory system, including everything from the ear up to the primary auditory nerve that sends signals to the brain.

The external part of the device, which hooks onto the user’s ear, contains a microphone, a battery, a computer processor, and an antenna. The microphone records audio and sends it to the speech processor, which then digitizes the audio and transmits the signal via the antenna. (The battery has to be replaced as often as every 14 hours, and most users carry around extra batteries with them at all times.)

Underneath the skull sits the internal implant that receives the signal from the antenna. The internal implant contains the “stimulator,” which is probably the coolest part of the device: It is literally the interface between the audio signal sent from the processor and the actual tissue of your auditory system. The stimulator’s goal is to mimic the pattern of electrical activity that the inner ear would normally be providing. The success of the stimulator is therefore solely due to our understanding, from a neuroscience perspective, of how our brains represent sound in terms of electrical activity.

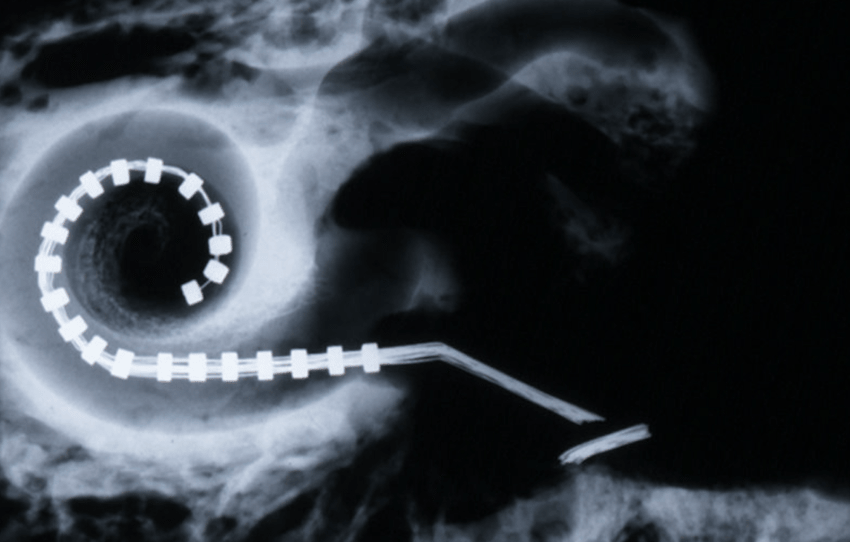

The stimulator is connected to 7-14 little metal electrodes that sit inside the cochlea (a hollow, spiral-shaped bone in your innear ear). The array of electrodes (which looks kind of like a little worm) is implanted, in surgery, by pushing the little worm thing inside your cochlea, not unlike a Babel Fish. The stimulator, once connected, then sends its signal to the electrodes, which then zap the cochlea. The precise pattern of zaps represents the sound recorded from the microphone in a way that can be processed by the brain as sound. Basically, this is done by splitting a spectrogram of the audio into pieces so that each electrode represents a different part of the spectrogram.

What they still can’t do

In a cochlear implant, each electrode is assigned to a range of frequencies, firing more to indicate when those frequencies are present in the recorded sound. But humans can hear a wide range of frequencies, so you might think that twelve electrodes is nowhere near enough to represent all of the sounds we can hear. And you’d be right! The main goal of cochlear implants is to recognize speech, and so the frequency range the electrodes represent is focused on that of human speech.

Because of this, the sound of a voice–though intelligible–sounds kind of like a demon’s voice: raspy, void of timbre and melody. Due to their limited ability to recognize pitch, cochlear implant users struggle with:

- identifying speakers identities or emotion by their voices

- perceiving/speaking tonal languages like Mandarin

- perceiving music

It may seem surprising that cochlear implant users “can converse relatively easily on the phone but cannot tell the difference between two familiar nursery songs.” Because there are only so many electrodes representing such a broad range of frequencies, a single electrode might be responsible for indicating an entire octave’s worth of notes–which means these notes would all sound the same!

Still, the amount of improvements in cochlear implants over just the last few decades is incredible. It’s truly a multi-discipline achievement, having required major improvements in surgery, engineering, and neuroscience.

Why aren’t there more neuroprosthetics?

Replacing parts of the body with electronic devices, known as neuroprosthetics, is a growing field. Other than the pacemaker and cochlear implant, though, why aren’t there more success stories?

Retinal implants, which attempt to restore vision in patients with certain types of blindness, have been around since the 1970s but are not yet useful enough to justify the risks of surgery and implantation, or the cost. On top of that, our visual systems are much more complex than hearing. While representing sound in a cochlear implant may only require 12 or so stimulating electrodes, retinal implants need 60 or more.

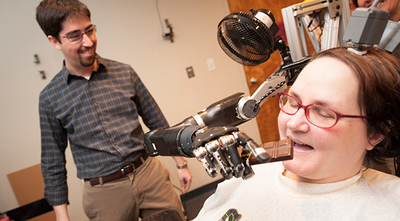

Brain-machine interfaces can also be used to sidestep the spinal cord, helping otherwise paralyzed patients control things like robotic arms. But again, these devices have a long way to go before they reach the general population. I think it’s fair to say that of all of our sensory/motor capacities, hearing just happened to be one of the easiest to understand, access via surgery, and engineer.

Summary

- Topic: Cochlear implants

- Why we care: They allow an otherwise deaf person to hear speech, via an electrical device implanted in their inner ear

- The ultimate goal: Improved hearing in noisy environments, and hopefully someday improved music perception!

(Un)related links

- My Bionic Quest for Bolero

- Stelarc, a performance artist who implanted an ear in his arm

- Neil Harbisson, who “sees” colors through sound

- The visual microphone, where ambient sound can be recovered from tiny movements in a plant’s leaves