Week #7: Cells

22 Jul 2018Paper: Origins of multicellular evolvability in snowflake yeast, by William C. Ratcliff, Johnathon D. Fankhauser, David W. Rogers, Duncan Greig & Michael Travisano (Nature Communications, 2015).

Soundtrack: “Something for your M.I.N.D.” by Superorganism

Cell life

What makes something alive? As you might have been taught through sheer repetition in grade school: The cell is the fundamental unit of life. In other words, by definition, all living things are made of cells. This is the reason things like yeast and plants are alive but rocks and oxygen are not.

The problem is, a cell is just an arbitrary collection of proteins and nucleic acids, which are themselves arbitrary collections of carbon, nitrogen, hydrogen, and oxygen, which are themselves arbitrary collections of protons and electrons, and so on. So in a way, saying that something is alive if it is made of cells is sort of a cop-out. After all, “cells” is the answer to a lot of other questions as well. (What is blood made of? Cells that can carry around oxygen. What is your brain made of? Cells that communicate via electricity. And so on.)

There’s an awfully large gap between a single-celled organism and a trillion-celled human. So how is it that a cell, a little self-sufficient entity made of DNA/RNA and proteins, can be an entire organism in itself (such as bacteria), but also the building block of all complex life such as insects and animals? How did life bridge the gap, evolving single-celled organisms into multicellular organisms?

Becoming multicellular

Over the course of Earth’s biological history, multicellular life has evolved from unicellular life at least 25 different times. Why did this happen? Under certain conditions, there must be a survival advantage given to cells that start to group up and specialize in different behaviors. For example, multicellular organisms tend to be larger, which probably make them less likely to be eaten.

But despite its apparent prevalance, the evolution of multicellularity has been somewhat tricky to explain. For a single-celled organism to become multicellular, it needs to develop cell-cell adhesion (so it doesn’t fall apart), cell-cell communication and division of labor (e.g., one cell might do the swimming while the other takes in oxygen), among other things. Each of these steps requires a coordination among cells that can be all too easily exploited by a rogue cell hoping to catch a free ride. The challenge, from an evolutionary standpoint, is to explain how the benefits of participating in a multicellular organism could outweigh the benefits of exploiting the collective.

Artificially evolving multicellularity

In this week’s paper, the authors examine how they were able to artificially evolve a single-celled yeast species into a multicellular one.

The authors first presented this result in their 2012 paper. The idea is simple, and pretty clever: Grow some unicellular yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae in a liquid medium, shake it up, and transfer these cells to a new medium. The cells will gradually settle due to gravity, with the heavier cells settling first. The authors then create an “artificial” (i.e., experimenter-controlled) selection pressure, by keeping only the lower 10% of the medium and throwing the rest out. Now, repeat! In this world, it is adaptive to be heavy, so that you sink quickly. If the unicellular yeast could somehow become multicellular, it would sink faster, and become more likely to survive another generation.

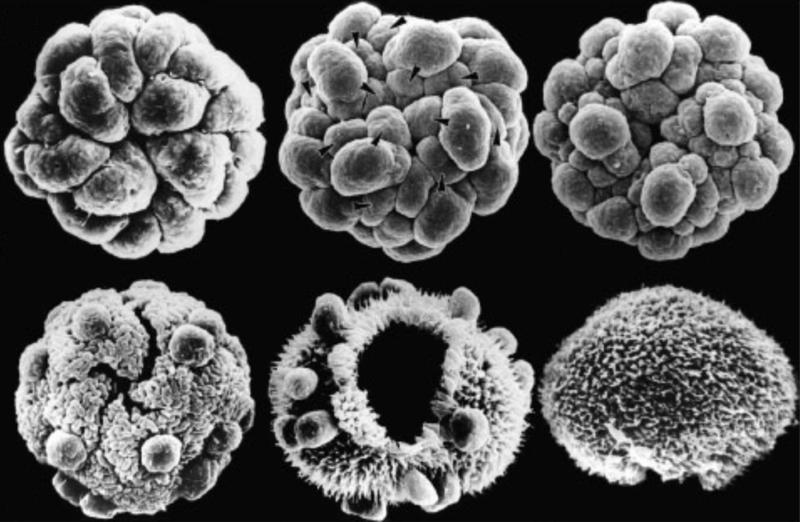

And in fact, after up to 60 transfers (one per day), the medium was “dominated by roughly spherical snowflake-like phenotypes consisting of multiple attached cells.” They repeated this experiment with 10 different starting sets of yeast, and ended up with this same result every time. In one population, they found multicellular yeast after only 7 days.

Snowflake yeast

You might imagine that multicellularity happens when two separate specialized cells come together and join forces. But in fact, multicellularity can also arise quite simply from an error in cell division. And that’s exactly what happens with these multicellular yeast clusters, which the authors call “snowflake yeast”. In short, every time a cell divided into two, the daughter yeast cell remained attached to its mother, physically (and probably also financially). Then the two cells divided again, and these daughter cells remained attached as well, over and over again until you have a big family tree of yeast. This evolved multicellularity appeared to be stable, because the yeast remained multicellular even when the experimenters stopped selecting for sunken cells.

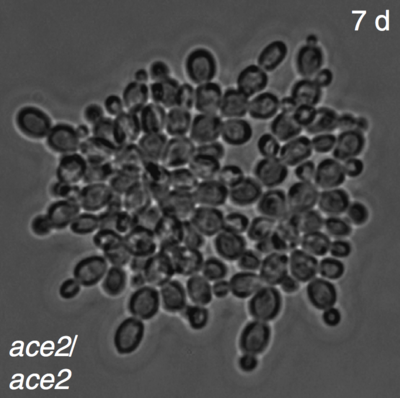

In their 2015 paper, the authors set about understanding what genetic changes enabled the yeast to become multicellular snowflakes. They compared the gene expression between the unicellular yeast and the evolved multicellular yeast. This led them to identify a single gene related to daughter cell separation that was being downregulated in the multicellular yeast, and they validated this finding by directly mutating the gene and showing it could make the yeast either cluster or not. So it turns out that the disruption of only a single gene was enough to make the unicellular yeast become multicellular.

In some ways, this might seem a little disappointing: The authors are claiming to have created a “multicellular” organism only because they’ve indirectly altered the gene that tells daughter cells to separate following cell division. But that’s not all that happens…

A family-tree made of yeast who never leave their parents

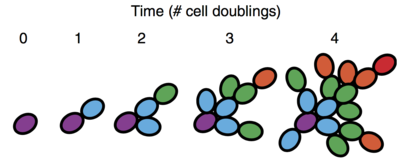

This simple mutation that causes new cells to remain attached ends up having a huge macro effect on the snowflake yeast’s structure. When a cell divides (purple cell in the diagram), the daughter cell (blue cell at time 1) remains connected to it. Later on, when the daughter cell divides, the grand-daughter cell (green cell at time 2) will be connected to the daughter but not to the grandmother. (The authors also provide a nice model of this structure based on Pascal’s Triangle.)

This family tree structure ends up giving these snowflake yeast two important characteristics. First, it gives them an easy way to reproduce: When a single cell dies, every cell descended from that cell will lose its connection to the main tree, resulting in a new independent cluster. In snowflake yeast, smaller clusters grew faster than larger ones, and so fracturing a cluster into two may sometimes be beneficial. In support of this, the authors found in their 2012 paper that apoptosis, or programmed cell death, co-evolved along with multicellularity. So rather than undergoing cell division to help grow the cluster, some cells die, which helps the cluster break into two. In this sense, apoptosis is a form of division of labor.

Second, and even more important, the family tree structure enables mutations to affect the entire cluster as opposed to just a single cell. Let’s say somewhere in the family tree, a mutation occurs in one of the cells. Let’s call this cell Aunt Edna. Over time, every cell descended from Aunt Edna will likely also inherit her mutation. If Aunt Edna dies, her descendents will break off, resulting in a new snowflake cluster all made of cells with the same mutation. To support this claim, the authors do a bit of modeling to show that in the long run, the snowflake yeast structure does indeed imply that clusters will eventually be composed of genetically identical cells. This is important because it means a single mutation can propogate to the entire cluster, which suggests the cluster itself is subject to selection.

Conclusion

The authors have shown that their multicellular snowflake yeast can effectively evolve as a unit, not merely as a collection of single cells. As they put it, these experiments “demonstrate that a single genetic change [can] create a new level of biological organization.” This simple genetic change caused:

- cells to cluster, becoming multicellular

- cells to have programmed cell death, allowing the cluster to effectively reproduce

- cells to be structured in such a way that allows mutations to affect the entire cluster

This highlights the fact that genes that have one effect in a single-celled organism may have a completely different effect in a multicellular one. This is in line with recent work published just a few months ago that found that a lot of the genes we once thought to be unique to animals are also present in simple unicellular organisms called choanoflagellates. This suggests that the evolution of multicellularity may not require as many genetic changes as we might think.

Summary

- Topic: The evolution of multicellular organisms

- The ultimate goal: Understanding how life evolved from single-celled organisms into single organisms made of trillions of cells working in concert

- Conclusion: Much of the complexity of multicellularity organisms may arise from simple modifications of genes already present in the unicellular ancestor

Related work

- More recently, the same authors evolved multicellularity in a more natural setting: predation. They took a single-celled algae called Chlamydomonas and exposed it to a population of paramecia that tend to eat smaller cells. Within a year or so, two of the five populations developed multicellular structures.

- Slime Molds Remember–but Do They Learn?, about recent work showing habituation (a form of learning) in a single-celled organism

- Programming self-organizing multicellular structures