Week #6: Plant intelligence

09 May 2018Paper: Plant behaviour and communication, by Richard Karban (Ecology Letters, 2008) [pdf].

Soundtrack: Journey Through The Secret Life of Plants, Stevie Wonder’s soundtrack to a documentary

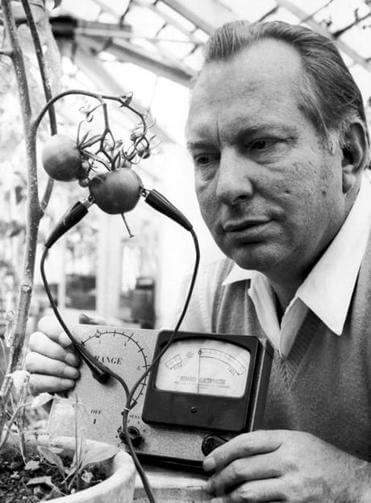

The last few weeks I’ve been thinking a lot about claims of “plant intelligence” and “plant communication.” I dug through more than ten different scientific papers, read about L. Ron Hubbard and his screaming tomatoes, and watched M. Night Shayamalan’s surprisingly entertaining movie (in a Troll 2 kind of way) about human-killing plant toxins called The Happening.

Clearly, plants are dumb, so the idea that they could be intelligent might sound like scientific click-bait. (And a lot of the time, it is.) On the other hand, plants really do have a lot of abilities that are pretty impressive, and so maybe calling it “plant intelligence” is just a way of inspiring new ways of thinking about how different types of intelligence might have evolved.

Overall, the tldr for this week is this: Whether or not plants are intelligent in an absolute sense, they are at least more intelligent than most people think. But that doesn’t mean you can pretend they’re Pixar characters.

Plants don’t care about music

Most discussions of plant intelligence start with the old wives’ tale that singing to your plants will help them grow, and that they might prefer Mozart to Metallica. This sort of mystical way of thinking about plants was popularized by the 1973 book The Secret Life of Plants, a book whose pseudoscience made it difficult for decades of biologists to claim any parallels between plants and humans without fear of being shunned.

But now the dust has settled, and many botanists are looking for more useful ways of thinking about plant intelligence. For starters: How should we define intelligence? 30-40 years ago, intelligence was something only humans had. Now, we might be more cerebrocentric and think that intelligence at least requires a brain. As I mentioned in last month’s email, one primary benefit of having a brain is that it permits fast movement. But plants are sessile (meaning they don’t move), so movement is clearly not a top priority* for plants, and so a brain might not serve much of a purpose. Instead, as plant biologist Anthony Trewavas suggests, maybe we should think of movement in animals as parallel to growth and development in plants.

* Unless you’re a venus fly trap, or a Mimosa pudica. In fact, though plants don’t have a brain, they do appear to also communicate electrically via action potentials.

While you can argue back - and - forth about whether defining intelligence for plants is even useful, the perspective many botanists have settled upon is this:

Definitions of `behavior' and `intelligence' vary. Intuitively we think of these terms as referring exclusively to humans, but essentially they describe the ability of organisms to respond to environmental challenges in such a way as to optimize fitness. Plants have similar properties.

Well-behaved plants

So our working definition of intelligence is that which gives you “fitness‐benefiting changes in behaviour: movement in animals, phenotypic plasticity in plants.” In other words, we can think of intelligent behavior as a response to the environment that has some evolutionary benefit. Though they may appear motionless, plants definitely have some pretty impressive ways of adapting to their environment. A non-exhaustive list of things some plants can detect:

- changes in daylength and temperature, allowing them to flower or germinate at the right time

- gravity, so they can grow their stems up and their roots down

- vibrations on leaves caused by chewing caterpillars, causing the plants to emit a chemical that the caterpillars find unappealing

- distributions of minerals in soil, which can be thought of as a type of “foraging” behavior

- the “smell” emitted by a damaged plant nearby, which some plants respond to by increasing their defenses

Can plants communicate?

This last plant ability I listed, that of “smell,” must have been the inspiration for The Happening, where plants learn to emit a chemical that kills nearby humans. But more importantly, this is also the entryway into the field of “plant communication.”

The idea that plants could communicate got off to a bad start in 1983, when the first reports on “talking trees” started appearing. The actual finding was that willow trees showed greater resistance to herbivores when they were nearby herbivore-infested willows than if they were further away. But the interpretation–that this meant trees were “communicating”–was not as solid. Since then, botanists have learned a bit more about the mechanism behind the effect, while also learning to speak in less provocative language.

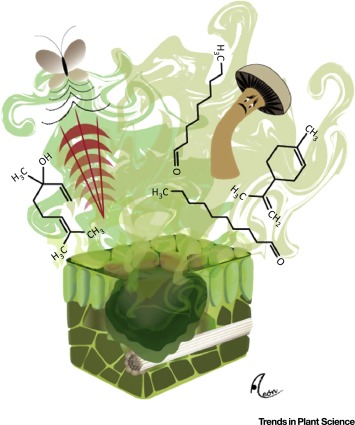

It turns out that when certain plants are damaged (e.g., by a caterpillar chewing on its leaves, or when one of its stems is broken), that plant releases a so-called volatile organic compound” (VOC) into the air. Other nearby plants can then detect these VOCs, and use these as cues to increase their own defenses, making them less likely to be attacked in the future.

But does this VOC signaling really qualify as plant “communication”? While this is an appealing conclusion (at least, I really wanted to believe it), there is one key problem with this sort of thinking: The benefits of VOC-signaling appear to only be for the plant receiving the VOC. The emitting plant could actually be endangering itself by releasing VOCs, because VOCs can attract parasitic plants or even more herbivores. Because “communication” is typically thought of as something beneficial to both parties, maybe we should think of this as “eavesdropping” rather than communication. In support of this interpretation is that the range of VOCs is very limited, and that VOCs have a stronger effect on more genetically-related individuals. This suggests that VOCs may actually be used primarily for signaling within a plant, rather than signaling to others nearby.

But what about my plant’s feelings?

Just because plants don’t have emotions or consciousness doesn’t mean there isn’t a definition of “intelligence” that might be useful scientifically. As Anthony Trewavas put it: “Different concepts and imaginative approaches are used in science because they suggest new experiments, new conceptual approaches and throw new light on complex problems.”

There are clearly a lot of behaviors plants have that you might not have expected. The problem is when the language we use to describe these behaviors start suggesting things that really aren’t supported by the research itself. So when you read, for example, that trees share resources through their roots, you might be tempted to conclude that “the trees in a forest care for each other.” But please…don’t.

Summary

- Topic: Plant intelligence and communication

- Why we care: Plants are the basis of most ecosystems, but the degree to which they modify their behavior in response to their surroundings is not well understood

- Conclusion: Describing plant behavior using human-centric words like “intelligence” walks a fine line between inspiring new research and becoming scientific click-bait

Image credits: [banner] [1] [2] [3]

(Entirely un)related links

- Quanta magazine, for consistently good science writing

- The impossibility of intelligence explosion

- Realtime MRI of someone speaking, and also this (nsfw) (other good videos here)

- An up-close look at tardigrades and their poop