Week #3: X-rays and crystals

21 Jan 2018Paper: Generation of High-Power High-Intensity Short X-Ray Free-Electron-Laser Pulses, by Marc W. Guetg et al. (Physical Review Letters, 2018) [pdf].

I got a bit in over my head this week, as most of the words in this paper were total gibberish to me. I got the main point: “We have a big laser and we made it more powerful.” But when I got to this paragraph, I kind of abandoned all hope:

"The energy chirp thereby links the dispersion with the beam yaw, which in turn allows the beam yaw manipulation through dispersion. Assuming a linear energy chirp, the beam yaw can be influenced linearly by the quadrupole tweaker magnet and quadratically by sextupole tweaker magnets."

Instead of talking about what a sextupole tweaker magnet is, I’m going to spend a lot of time talking about the basics of x-ray crystallography, which is ultimately what the laser in this paper is used for. After that, I’ll talk briefly about the laser itself, and what they did to improve it.

X-ray laser crystal stuff

I know I’d heard the words “x-ray crystallography” before this week, but I don’t think I had a clue what an impact this concept had on almost all of biology and chemistry. Research using x-ray crystallography has led to more than 25 Nobel Prizes; it’s how we know the size of atoms, and it’s also the way we know the chemical structure of most drugs and proteins. In fact, an image of DNA taken with x-ray crystallography is what led to Watson and Crick’s development of the double helix model.

To understand what an impact this has had on science as a whole, consider that the most cited paper of the last two decades is about a software package used for x-ray crystallography.

At a very high level, in x-ray crystallography, you shoot lasers through a crystal, and the resulting diffraction pattern tells you the atomic structure of that crystal. This sounds somewhat unimportant until you realize that almost everything can crystallize: not just familiar crystals like salt and ice, but also semiconductors, metals, proteins, and all sorts of other biological materials such as viruses.

(Fun fact: The development of protein crystallography was due to Dorothy Hodgkin, who first used x-ray crystallography to determine the chemical structure of penicillin and insulin. In 1964, she became only the third woman to earn a Nobel Prize.)

I forgot what an x-ray was

I’ll admit, at first when I read “x-rays” all I could think of was dentist and airport visits.

An x-ray is just the name for light that has wavelengths shorter than UV and visible light but longer than gamma rays.

Their short wavelength is the main reason we can use them for imaging: They can penetrate materials without being absorbed (too much) or scattered. Because the wavelengths of x-rays are so close to the size of atoms, we can also use them to determine crystal structures.

(A longer aside: Light with shorter wavelengths also have more photon energy. Because of this, x-rays are a form of ionizing radiation, which means they rip electrons off the atoms they pass by. But we didn’t always know this. In the 1920s-1970s, shoe stores used to have x-ray machines called “foot-o-scopes” that they’d use to find your shoe size. This seemed like a less good idea once we learned about the effects of radiation.)

Crystals and diffraction

Okay, now for a little bit about crystals. (“I invite you to enjoy the beauty of my crystal…”) Crystals are such a great example of a subject where a branch of abstract mathematics (group theory) actually ends up predicting parts of the observable, natural world. A crystal is just a regular, repeating arrangement of atoms (or molecules, or ions), and we classify them by their repetitions, or symmetries. But from group theory, we know that in 3D space, there are only 219 different symmetries possible. In a sense, this means we can actually know every possible type of crystal that exists, before we’ve even encountered them all. Imagine if the same were true of other things—say, if math could predict every type of animal species.

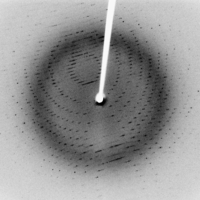

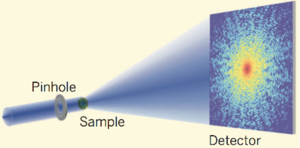

So, in x-ray crystallography, we shoot x-rays at a crystal with a laser, and what we get is an image of the diffraction pattern, which basically looks like a scattering of dots. The scattering occurs because x-rays interact with the atoms in a crystal system, according to “Bragg’s law”. Because of Bragg’s law, the brightness of the spots in the image actually represents the density of electrons at different parts of the crystal we’re imaging.

If you’re interested in the math of how this works, it turns out that the brightness of the spots actually represents the coefficients of a Fourier series describing the electron density. (There are some good descriptions of this process here and here.) And once you’ve computed the density of the electrons from the diffraction image, you can then work out the chemical structure, by some other equally complicated process.

The x-ray free-electron laser

This paper is about an x-ray free-electron laser at the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory near Stanford. The laser, called LCLS, is the most powerful x-ray laser of its kind. (It’s also two miles long.)

The reason you want to have a powerful laser in this case has nothing to do with military might, but instead with image resolution: The goal of a free-electron laser is to send a brief but powerful pulse of electrons at whatever it is you’re trying to image. You can think of the pulses as being the shutter of a camera: With just a single brief pulse, we can get the diffraction pattern we need to image a virus, or whatever it is we’re interested in.

By a “brief” pulse I mean one that lasts 1/10th of a trillionth of a second (or 100 femtoseconds). In this amount of time, electrons actually move quite a bit, and so if you deliver slower pulses you’ll get a blurrier image. (Another reason not to send slower pulses is your specimen will explode into plasma before you can get the image.)

But the briefer the pulse, the more intense you need the power of that pulse to be. According to this paper, the peak intensity of the pulses are limited by something called the “beam yaw,” which is what they go on to fix, using previous theoretical work. Long story short, “We have a big laser, and we made it more powerful by aligning it better.” Sorry to make it sound so incredibly simple, because it is anything but that.

Summary

- Topic: A free-electron laser for x-ray crystallography

- Why we care: Shorter and faster laser pulses will give us better image resolution, enabling better imaging of super tiny molecules and other tiny things

- Conclusion: Adjusting the beam’s yaw, along with a few other technical adjustments, yielded a higher peak intensity in each laser pulse

Related links

- Examples of every possible crystal symmetry [pdf]

- 3D tour of the LCLS [link]

- Recent x-ray laser experiments at LCLS [link]

- Protein crystals grown on the outside of the U.S. and Russian Space Stations [link]

Coming up next week: self-driving cars